Mr. Creep and the Undermining of Variable Speed Curve Control

/We call him Mr. Creep.

Mr. Creep is not an actual person but rather a phenomenon of an ever-increasing control head in a variable speed pumping system caused by frequent incidents of underflowing coils, the result of which is progressive increases in operating cost and potential non-compliance with ASHRAE.

(See why we prefer “Mr. Creep?”)

Clearly, the above explanation is a little convoluted, not to mention a real mouthful. But don’t worry, we’re going to make sure you get clear understanding of who Mr. Creep is and why you don’t want to invite him to your next office party or even into the building.

If you’ve been with us throughout this most recent series of blogs on variable speed pump control, you should be familiar with what “misses” are and how and why they occur in curve controlled systems. (If not, we recommend reading the linked blogs at the end of this article.) Hopefully, you also understand that misses are a fairly common occurrence in variable speed systems that rely on a curve control strategy.

When misses occur, coils can become starved of flow. This results in unsatisfactory space temperatures and often uncomfortably high humidity levels, which leads to a lot of complaints from building occupants. The inevitable response to these persistent complaints is to increase the control head on the pumping system. Over time these adjustments cause the control head to “creep” up, sometimes exceeding efficiency parameters set by ASHRAE, which as we learned in an earlier blog typically require a control head of no greater than 40% of the total system head.

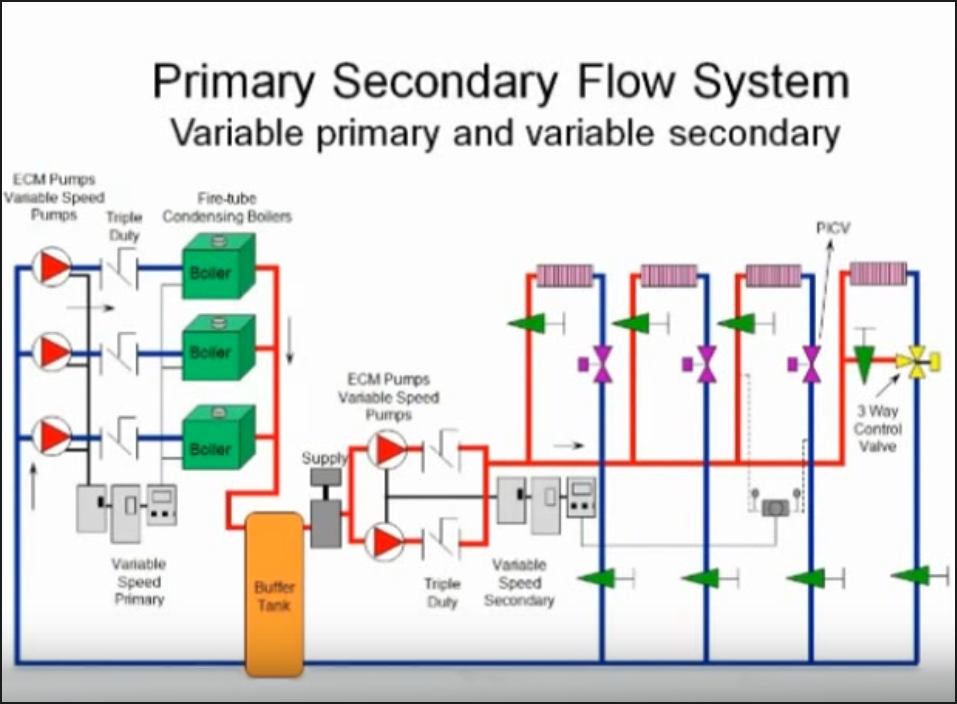

To illustrate our point, let’s say we have a system that utilizes a curve control strategy – in this example one that relies solely on manual balance. In the system below, what happens when the only zone calling for full flow (200 GPM) is Zone A, closest to the pump?

If we have manual balance valves, we are going to need 68.7 feet of head to overcome the resistance in Zone A. But remember, if our curve pump control typically automatically defaults to 40% design head (we covered this in our last blog) we will only have 36 feet of pump head available. By using the System Syzer we can see that we will only have 145 GPM of flow thru the coil.

Therefore, we are short of the required flow in Zone A, even though it is the only zone calling for flow. We call this a “flow miss” and depending on the coil flow tolerance, we are most likely going to have unhappy occupants.

This is when the complaints start to pour in and Mr. Creep “fixes” the situation by increasing the system control head. Typically, these increases to the control head will continue until there are no more complaints. Everybody is happy, but operating costs sky rocket because we are over-pumping the system. Furthermore, we are most likely no longer ASHRAE 90.1 compliant.

We are seeing more and more of “Mr. Creep” in hydronic systems today. This reason is largely due to the increasing presence of curve control variable speed pumping systems. The strategy has been widely embraced, but not necessarily fully understood. Curve control is not a one-size-fits-all solution. At JMP, we advocate the following guideline:

“If your control area is big AND you have high diversity, do not use curve control.”

In these cases, variable speed area control will provide better energy optimization and comfort. Stay tuned for more on that in our next blog!

For more information, check out these recent blogs:

Variable Speed Pump Control: How Variations in Demand Load Define the Control Area

Diversity in a System with Variable Speed Pump Control

Flow Tolerance in a System with Variable Speed Pump Control

Manual Versus Automatic Balance in a Variable Speed Pump Control System